Dailan Pugh Artworks

See My Works

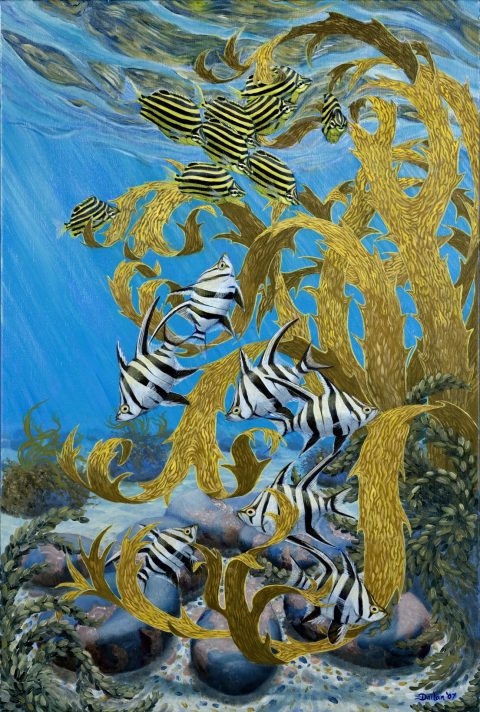

With my artwork I am endeavouring to awaken people to the beauty and intricacy of our natural world while developing a style derived from this primal source

About Me

Dailan is a passionate conservationist, his love of the natural world and his desire to depict it, has led him down life’s path. He is awed by the vibrancy of the natural world across its spectrum, from deserts to rainforests, and down beneath the waves. His dismay at the carnage and degradation he has witnessed has forced him to spend more time on activism than his art. His desire is to use his art to awaken people to the beauty and intricacy of our natural world while developing a style derived from this primal source. He was awarded an Order of Australia Medal for his services to forest conservation in 2004.